Yaccarino's real job at X: Wrangling Musk

The unspoken line item in every woman's job description? Being Mom.

When I was offered the first real promotion of my employed career, it was framed as a great thing for me (and well-deserved because of me) for about 10 seconds until it was revealed why I was actually being given the gig. An extremely talented but unmanageable colleague in the department had driven off the latest in a line of supervising editors. These editors had done quotidian things like enforcing the very reasonable rules and regs of journalism (and physics) only to have this impish writer go into a thrice-edited story and, against all known norms of journalistic mores, restore an excised 15 inches of breathless expository on an obscure jazz musician when I had already begged, borrowed, and stolen 22 additional column inches for a piece I originally assigned as “30 inches, tops, please, it’s already way more space than anyone else is getting this Sunday,” leaving me to deal with the press room when they’d inevitably call up and ask about the large block of type that read “OVER BY 14,689 LINES” on the 67-inch magnus opus that was only supposed to be 52 inches long (only!), and that was already 22 inches of attention span longer than it should have been because not only is newsprint expensive but we have to be, um, you know, and I am so sorry about this, mindful of what newspaper readers actually want to read. We have to – I know, I know, they’re such philistines – give them relevant things or they may decide we’re no longer relevant and then newspapers might not exist anymore. Making me the Chicken Little of lower management, the buzz kill, the rule follower. The mom. I was being named mom of the department in hopes of reining in the id of a wordsmith continually delighted with all he (surprise! it’s a he) had to share with our readers. If this were a sitcom, he’d be Tracy Jordan and I’d be Liz Lemon. Or maybe it was more Ted Baxter and Mary Richards. Whatever. And if it sounds like I’m holding a decade-old grudge against the writer, let me make myself clear: My beef is with the middle manager(s) who came up with the deliciously devious idea of putting me in that position, knowing that, as a young woman, I’d contort myself into a pretzel, on the daily, trying to both appease and control (impossible) this enfant terrible.

[OMG, the moment when Sorkin brings his hand to his face at 0:37.]

Which is not to say that I completely sympathize with Linda Yaccarino. She was much older, much more experienced, and already had an impressive gig when she was offered the job of CEO of what was then called Twitter. If she didn’t know she was being asked to deal with tech’s most incorrigible bad boy, to be Elon Musk’s apologist in public and mom at the office, then I don’t know how to help you, Linda.

Today I’m feeling mega-grateful I was only the handler of a self-important critic gassing on about the ethereal beauty of Dakota Fanning. I didn’t have to play cleanup when my boss told Disney’s Bob Iger and other advertisers to go fuck themselves. Or called my interviewer by the wrong name.

I’ve also never been handed X’s most massive challenge (whether or not Yaccarino sees it as such; it’s unclear): the danger of a social media platform hosting misinformation, disinformation, antisemitism, and other content that threatens thing like public health and our democracy.

But I do recognize the desperate tap dancing Yaccarino is doing (unconvincingly and not particularly well). Because that is what we’ve actually been hired to do. That’s why we were offered the job.

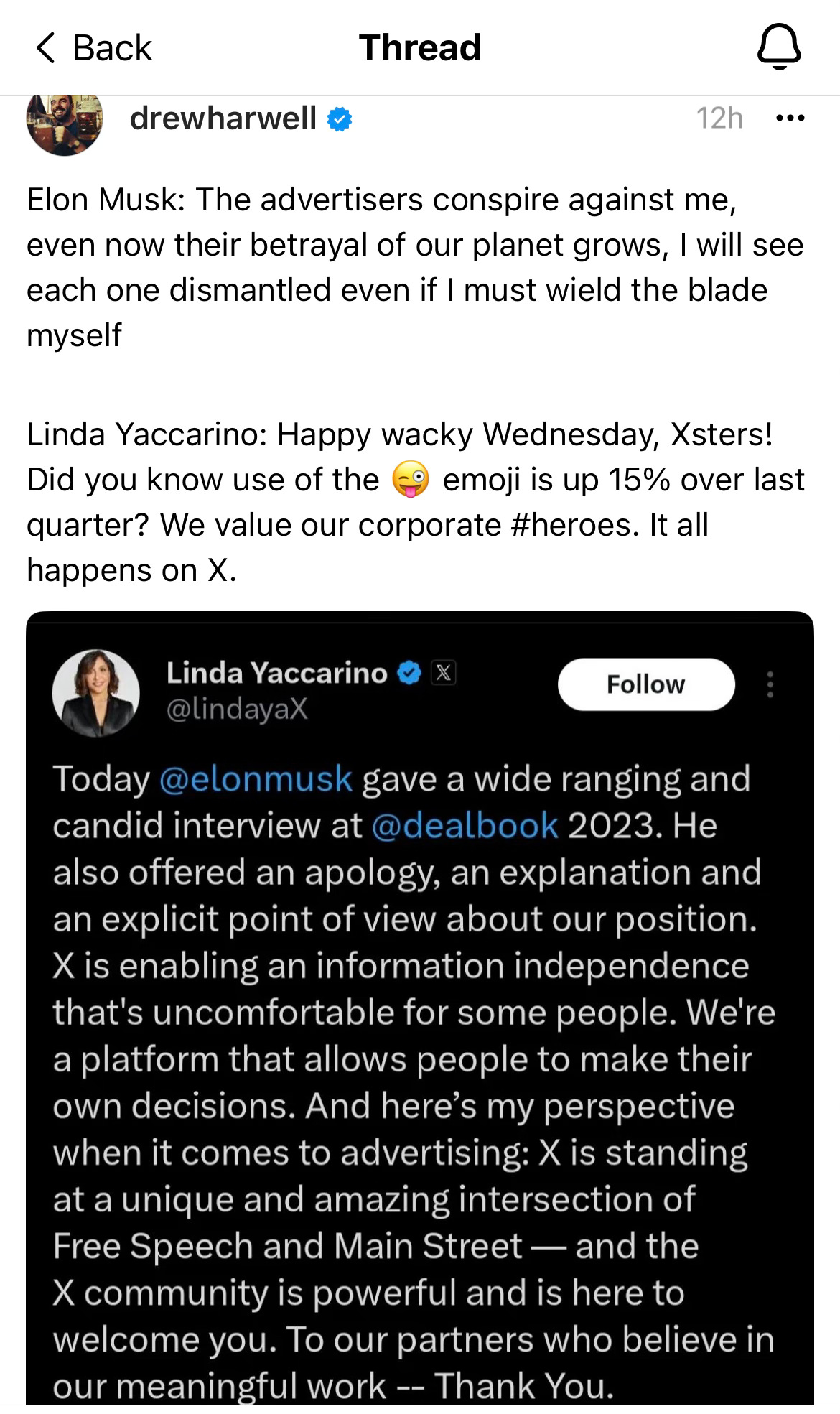

She’s being paid a hell of a lot more than most of us and she’s doing this tap dancing in a plush C-suite (with an extra sink?), but Yaccarino’s explaining away of her boss’ “wide ranging and candid interview” is the unspoken line item in every woman’s job description. We know what’s being asked of us, and we do it for the department, for the company. We do it because letting the boss hang himself doesn’t do any good for the people we work with, and that’s who we really care about.

We’re given the jobs of wrangling the delusional because it’s well-known that we’d rather literally die than let someone else look foolish or be uncomfortable for even a second. We’ll put to work all the accommodation skills we’ve learned from girlhood – how to ignore and redirect questionable behavior, how to mask any indication that we’re offended, how to smooth over someone else’s verbal gaffes or outright rudeness, how to wave it away with an oh, no, he didn’t mean that. We’ve been doing it all our lives. We do it when our husbands tell a joke that bombs at a neighborhood party, we do it when the boss asks a pregnant colleague if she plans on working after maternity leave.

There are times I suspect that this is our true perceived value, what they bring us in for, how we really earn our promotions – for handling the interpersonal stuff, the touchy-feely, the tricky assignments and difficult co-workers no one else feels they get paid enough to deal with.

As chairman of global advertising and partnerships at NBCUniversal, Yaccarino’s extrinsic value was in increasing ad revenue. (That may have been a priority when Musk hired her last year, but he seems to have since decided advertisers are blackmailing him?) But her real purpose was to provide the necessary balance to allow Musk to be candid and let fly. Her value was in the intangibles – optics, explaining, smoothing. A woman’s touch.

In my case, in that newsroom where I sat, eager and fresh-faced, my ambition was wielded against me to take a job no one else wanted. To get me to stay in the job, they weaponized my agreeability, my innate desire to be likable.

If you think you couldn’t be paid enough to deal with someone like Elon Musk (and you’re a woman), look around at who you are dealing with. Whatever your sex or gender identification, whatever you do for work, ask yourself this: How much of my job involves managing behavior, feelings, and perceptions? If you tell me how you identify, I can tell you exactly how much.